The joys of math

Years ago (whoa!) I was a grad student suffering through some difficult math courses. I didn’t understand what we were being taught, which made me feel extremely dumb and insecure. Granted the goal wasn’t to understand the math at a deep level; the goal was to conduct original academic research. Any math we learned was aimed toward this end.

Still, I constantly had the feeling that there was something more interesting behind the symbols. I sensed it in the way my professors perked up when they talked about them, free from their research agendas and university pressures. It seemed as if they were reconnecting with lifelong friends. Sarcasm, wit, intimacy, reverence even characterized their relationships. Wtf is going on up there, I often wondered. What are they seeing that I can’t?

Mathematica: A Secret World of Intuition and Curiosity by David Bessis, gets at this question. It’s a craft/process book of sorts, a glimpse into what’s happening in the mind of mathematicians when they do math. According to Bessis, the experience is less like “a series of discouragingly incomprehensible logic problems” than it is “a physical activity akin to yoga, meditation, or a martial art.” What does this mean exactly?

The schooling I (and many of us) got in math was very boring. I got good at solving problems through the rote application of “tricks”, moves, techniques that were foreign to me, but I never felt like I was learning anything significant. Math was just another hurdle to fumble over before I got to play more video games. Such was the bulk of my math education. People who enjoy math experience it differently.

When Bill Thurston was a kid, his father asked him on a long drive: what is the sum of 1 to 100? (We’re thinking only of integers here.) He thought about it for 3 seconds or so, and then answered 5000. “Wrong,” his father said. “Think about it some more.” Another second or two passed before Bill gave the right answer: 5050.

It’s an impressive feat, especially if you think that the only way to solve this is to mechanically compute the sum. Like, adding one number with the next (1 + 2 = 3; 3 + 3 = 6; 4 + 6 = 10; 5 + 10 = 15; …), keeping track of the total as you go, and repeating until you reach the end of the sequence. Maybe some people can do this, people with extraordinary working memories, as if they were actual computers. But it’s more likely that he had the right abstraction or mental image in mind, a refined intuition for how to think about the problem. This, in turn, enabled him to answer the question quickly. The question then becomes how he came to develop this intuition.

Bessis writes a lot about the familiarity that mathematicians have with the math. What I think he means is: they understand what it means to add stuff together, for instance. They have a feel for the objects that they’re working with, much like how poets have a feel for words and the effect of their infinite arrangements.

If they don’t the work is to develop this feel. It’s to create a clearer sense of the elements involved and how they fit together. The logic and formalisms most people associate with math are simply tools in service of refining intuition. Once this is in place the answers sometimes literally fall into their lap. This is the eureka moment, the high that mathematicians chase. Refining your mathematical intuitions probably won’t turn you into a fields medalist, but it can add to the total sum of joy in your life.

I wrote earlier that I learned a lot of “tricks” in school, and that this is how many people are taught math. For young Bill Thurston’s problem, you might be told that you can get the answer by following this trick:

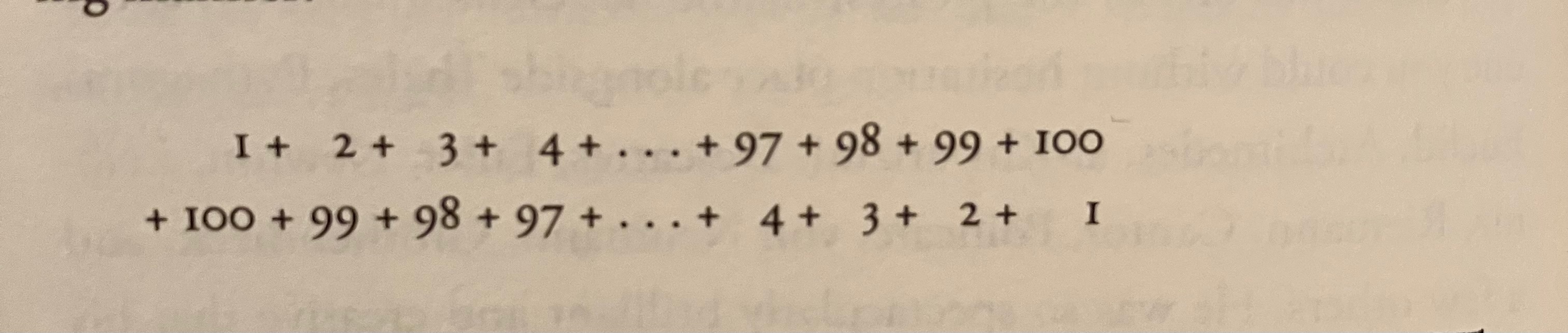

Write out the sum of the sequence on one line (e.g. 1 + 2 + 3 + … + 98 + 99 + 100)

Write out the sum of the same sequence but in reverse (e.g. 100 + 99 + 98 + … + 3 + 2 + 1) on the line under the first sequence

Line up the numbers in each sequence so that you end up with 100 “columns” (1 with 100, 2 with 99, and so on. See image below)

Notice that every column adds up to 101, and that there are 100 columns

Adding all of these columns together is the same as multiplying 101 x 100

This is double the sum we want because we are adding the same sequence of numbers twice

So divide this sum by two to get the sum we actually want, i.e. (101 x 100)/2 = 5050

One takeaway is that it’s easier to do this problem in terms of multiplication and division, rather than adding up 100 numbers together. The trick is to reframe the problem so that it’s more intuitive.

Ok cool. But how in the world would you ever arrive at this “trick”, this intuition? Only a weirdo nerd genius would have come up with something like this! Maybe that’s true. I’m not discounting the existence of such people. But if you spend some time thinking about the problem, you may realize that the solution depends on having an understanding of what it means to add stuff together—more specifically what it looks like, in my case.

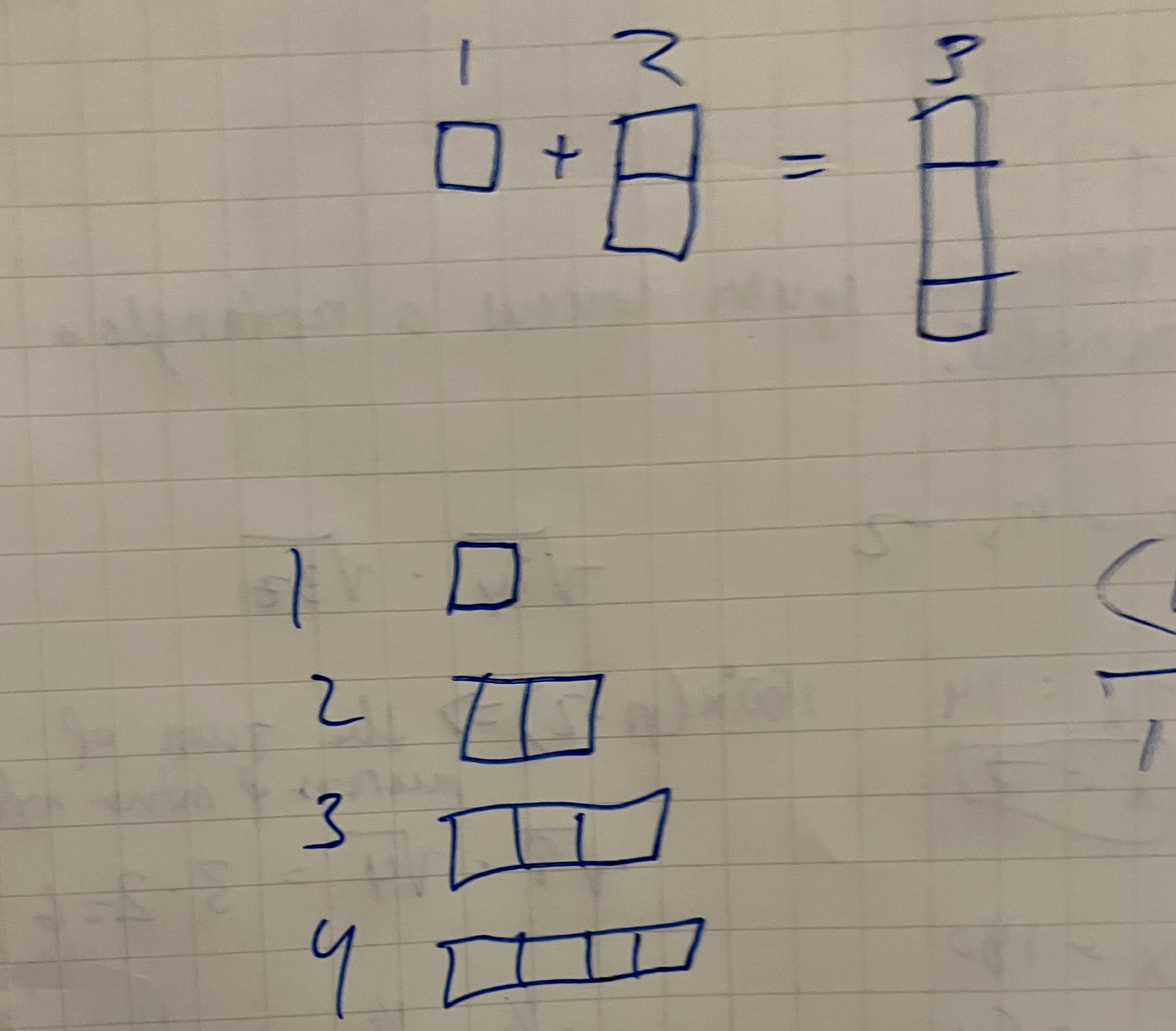

After laying out the above (paraphrased) procedure, Bessel encourages the reader to pause and think about how you might arrive at the same answer. So I closed the book and looked out of my window for a bit. I thought very basic thoughts like “the sum of something is a bunch of smaller stuff put together” and “the numbers in this sequence are one bigger than the previous.” I tried to visualize this and imagined blocks of increasing size being stacked on top of one another. The sum of something is a bunch of smaller stuff put together…

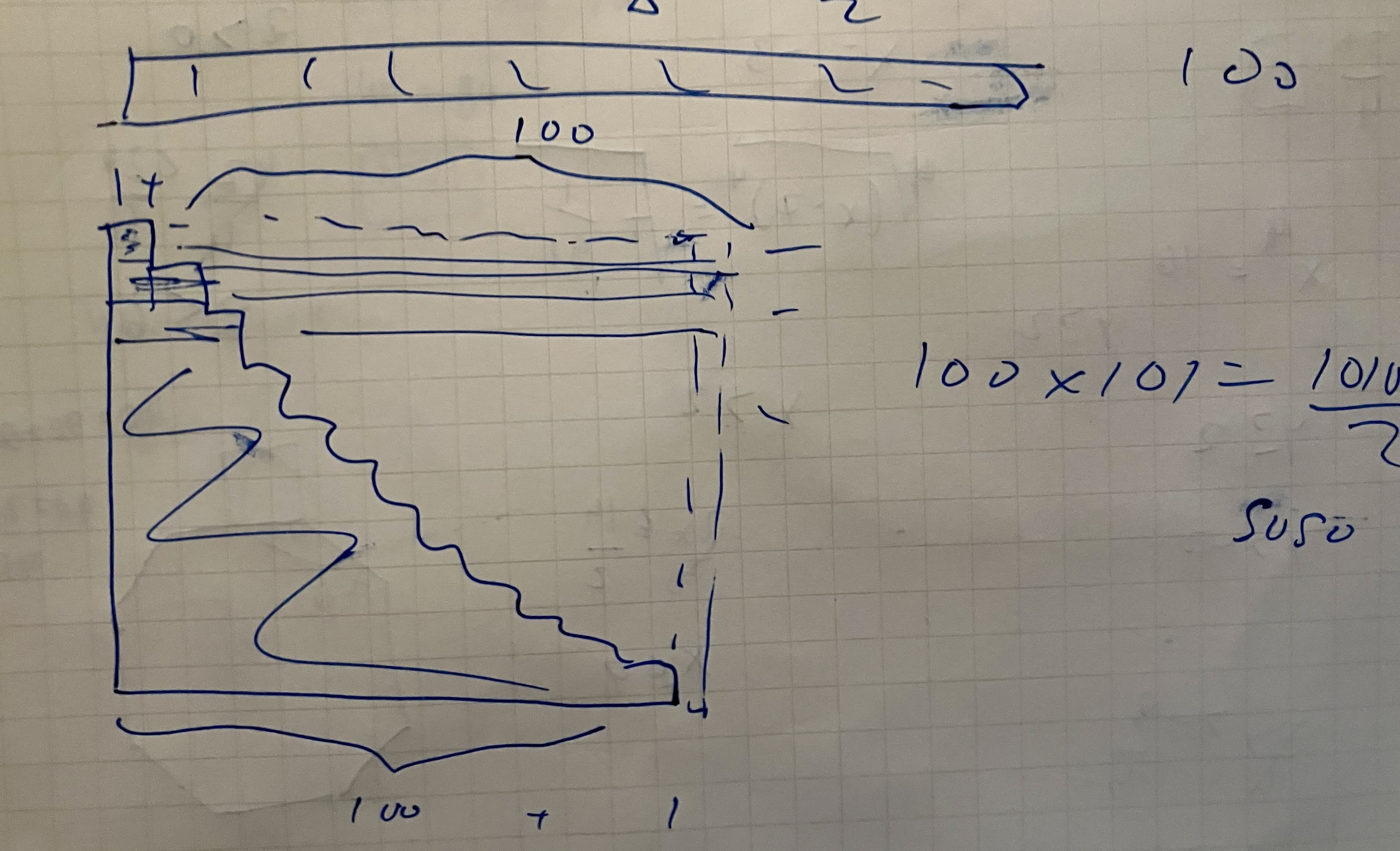

I then wondered about why the sum was doubled and what that would look like. The stacked blocks in my head had formed a kind of triangle. This blocky triangle corresponded to the sum of one sequence (1 + 2 + … + 99 + 100). Reversing the sequence and adding it to the first—would that correspond to “gluing” a flipped triangle to the other? And then it hit me.

Yes! It did! It had to! It formed a square! Oh wait—no, a rectangle with a width of 101 and height of 100! The area of this rectangle is double the sum we want! And cutting it in half gives us the sum we want! It gives us back the original blocky triangle! Wait another connection! The calculation (101x100)/2—this is the formula for the area of a triangle! EVERYTHING. IS. CONNECTED!!!

The euphoric sense of “this all makes sense” came long before I verified my intuitions with the sketches above. It was a process that felt like one of curious play, like a part of me was patiently poking at the abstractions that were somehow generating themselves. I wasn’t in control. I simply let the shapes and objects rotate themselves, until something locked itself into place. The image and problem suddenly became very clear. It was like a truth I couldn’t unsee. What followed was a stupid, giddy, guiltless joy. I couldn’t sit still. I felt like a loved child on Christmas morning.

Coming down from my high, I started wondering if I had cheated somehow by being primed by the “trick.” Part of me wanted the purity of discovering what I discovered without any outside influence. It was also obvious to me that my discovery would be elementary to a seasoned mathematician. But I quickly realized it didn’t matter. What mattered was that I had attempted to develop my own intuition, that I had discovered something interesting and true, and that it was joyful.

The joy of math resides in working something out for its own sake, in choosing to play with an attitude of curiosity and determination. This is true beyond math as well. Anything approached as a dialogue between your intuition and the effort to refine it is bound to be a rich adventure. Doing math is precisely this dialogue, according to Bessel.

Schools focus too little on the intuition part, which is why most people find math so boring and difficult. I’m glad I get it now though, the way that my professors probably felt at first when they were budding math students. You get to constantly feel like you’re on the verge of something new and beautiful, like some piece of the grander puzzle is about to click into place. Sometimes, after a degree of effort, efforts that may require a lifetime, the truth emerges, or at least some fraction of it. It’s not guaranteed, but it’s definitely worthy of trying.

A question that keeps nagging at me is if I’ll do more math. I’m not so sure right now, to be honest. I like moving at my own pace, and the expectation that an experience like this should immediately turn into a thing is one I’m wary of. That said: what a crazy wonderful thing it must be to live a life guided by the sound of this ongoing conversation. It’s hard to see that it is happening, that something is happening, but the motions are there, being engaged by all of us in one form or another. For some it manifests as math, and it can be many more if we’re curious enough to find out what it’s truly like. For me, it’s pretty sublime.