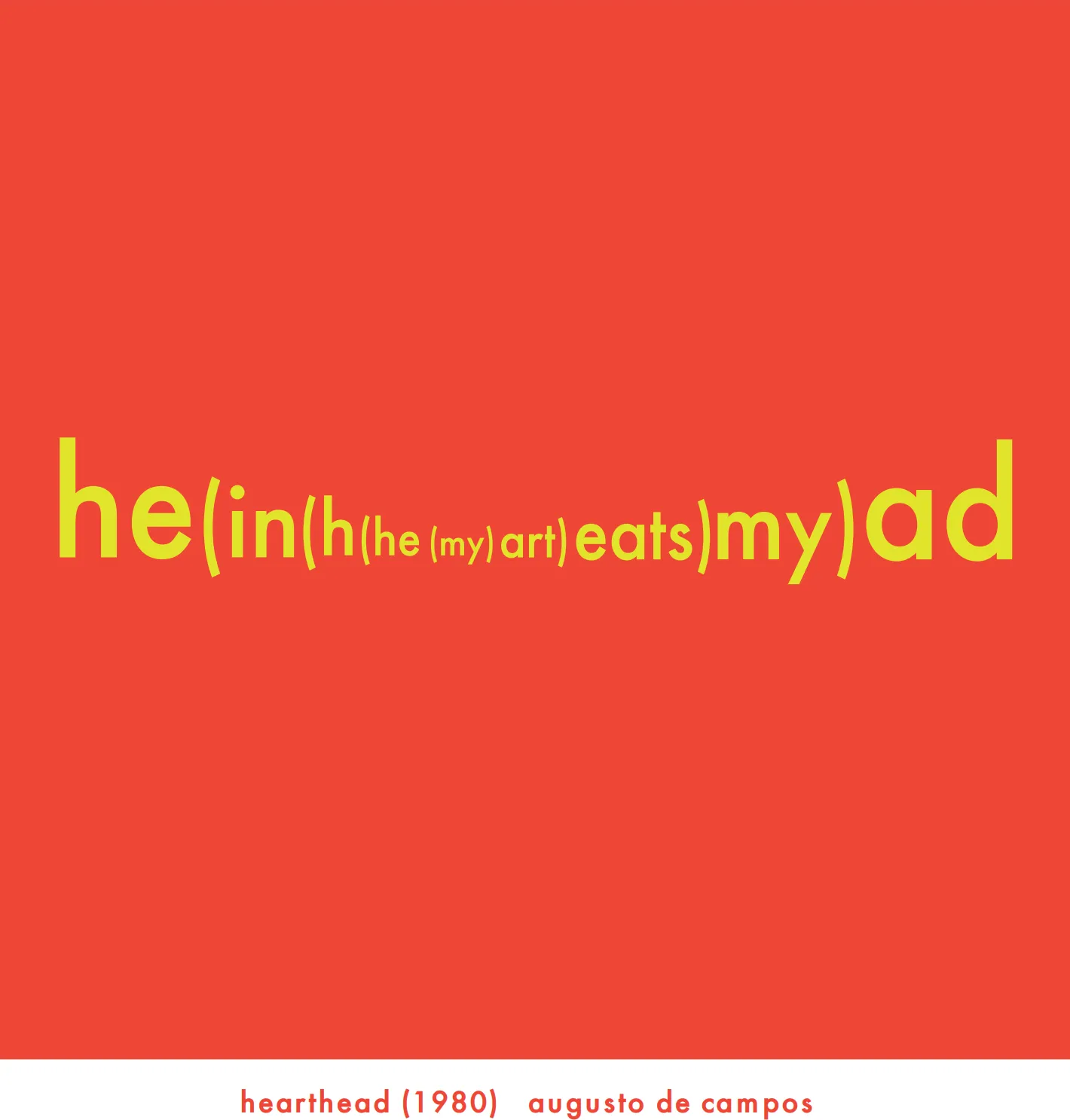

hearthead (1980)

I recently started reading Real Toads, Imaginary Gardens: On Reading and Writing Poetry Forensically by Paisley Rekdal. I like this book over other “about poetry” books because she approaches it like a forensic scientist, with a focus on craft and process. Gregory Orr’s A Primer for Poets & Readers of Poetry, for instance, moves the Rilkean in me, but it doesn’t quite jive with how I typically build an understanding of things. I like people to take baby steps with me, to really explain, bit by bit, all the elements of a thing and how they hang together. This is true whether it involves math, meditating, or poetry. Sometimes, I need someone to show me how to experience something new.

The first exercise I did felt like this. Rekdal focuses on honing what I’ll call “the movements” of reading a poem, the mechanics of what you might want to do upon first encountering a work. Here’s the exercise:

Select one work from the list of shaped or visual poems below and write down all the things you notice about it. Where does your eye go first? How does your eye move around the page? What differences in typeface or font do you notice? What is legible to you and what isn’t? How does the title influence what you see? Are there different kinds and types of language in the poem? Is the poem composed of different kinds of physical material? Is there any relationship you can discover between the shape of the poem and what is being said?

I ended up choosing “hearthead” by Augusto de Campos, just because I liked the title. Here it is below, followed by my (mostly) spontaneous response to it.

The outer layer is what hits me first, the “he(” and “)ad”. My eyes are moving outside in, from left to right, and then I notice the perfect contrast between the yellow text and the red background.

The words “art” and “eats” are what I see next, and how the words grow smaller and smaller the more inward you look. It feels as if I am looking from a distance, from the distance of the outer layer where “head” is registered as a word, where my head is registering, something. My head is closer to me, to the outer layer, far away from where the juice of the poem might be. This feels like a dismissal of the poem as a whole, though is the form telling us something about the heart?

I look away and look back quickly. The phrase “head in my heart” immediately presents itself. This makes me wonder if it’s easier or more difficult to find the reversed phrase “heart in my head.” The former certainly feels easier to find in a literal sense, in the physical motions of my mind, which is brilliant on the part of Augusto, and also, since poetry is a two-way street, it says something about me, about my heart, maybe. The poem becomes less delightful when I think about it too much.

“Eats” comes back again when I look up, and I laugh. It’s like the head has eaten the heart, and art too. The words “my” and “he” are repeated throughout, and I wonder about their significance. My attention turns toward the parentheses shortly after, reminding me of waves being transmitted from a radio tower. Is the heart like a radio that sends us messages, small and subtle ones that aren’t always easy to hear?

I look at the size of the words and their off-center orientation. Looking at them makes me feel like I am walking down a hallway, or seeing something far away. What is being seen, attempting to be shown? The word “my”, “my” separating heart into he and art. A tragedy in one sense, but also something beautiful in another: art. He is alone without art. He and art combine to make heart. His heart—the heart—needs art to be complete. It exists separate inside my head.

I move my head back from the screen and recognize there is a difference when writing from my head than my heart. I only scratch the surface, the outer layers, with my head, while everything that comes from my heart is more like art. Look superficially and all you get is the head. It takes a closer to look to find the heart, the art that lives within. But you need both, it seems. Or not. Perhaps the heart is constrained by the head, and sometimes that is what it needs. Art, and life, cannot exist without constraints.

This was a really fun exercise for me. Try it! The other poems Rekdal suggests to do this with are:

- George Herbert, “Easter Wings” and “The Altar”

- Douglas Kearney, “Falling Dark at the Quarters”

- Anthony Cody, “Cada día más cerca del fin del mundo”

- mIEKAL aND, “mi’kmaq book of the dead”

- Eugene Gomringer, “Silenco” and “o”

- Scott Helmes, “haiku #62”

Let me know how it goes. Happy New Year!