Chaos

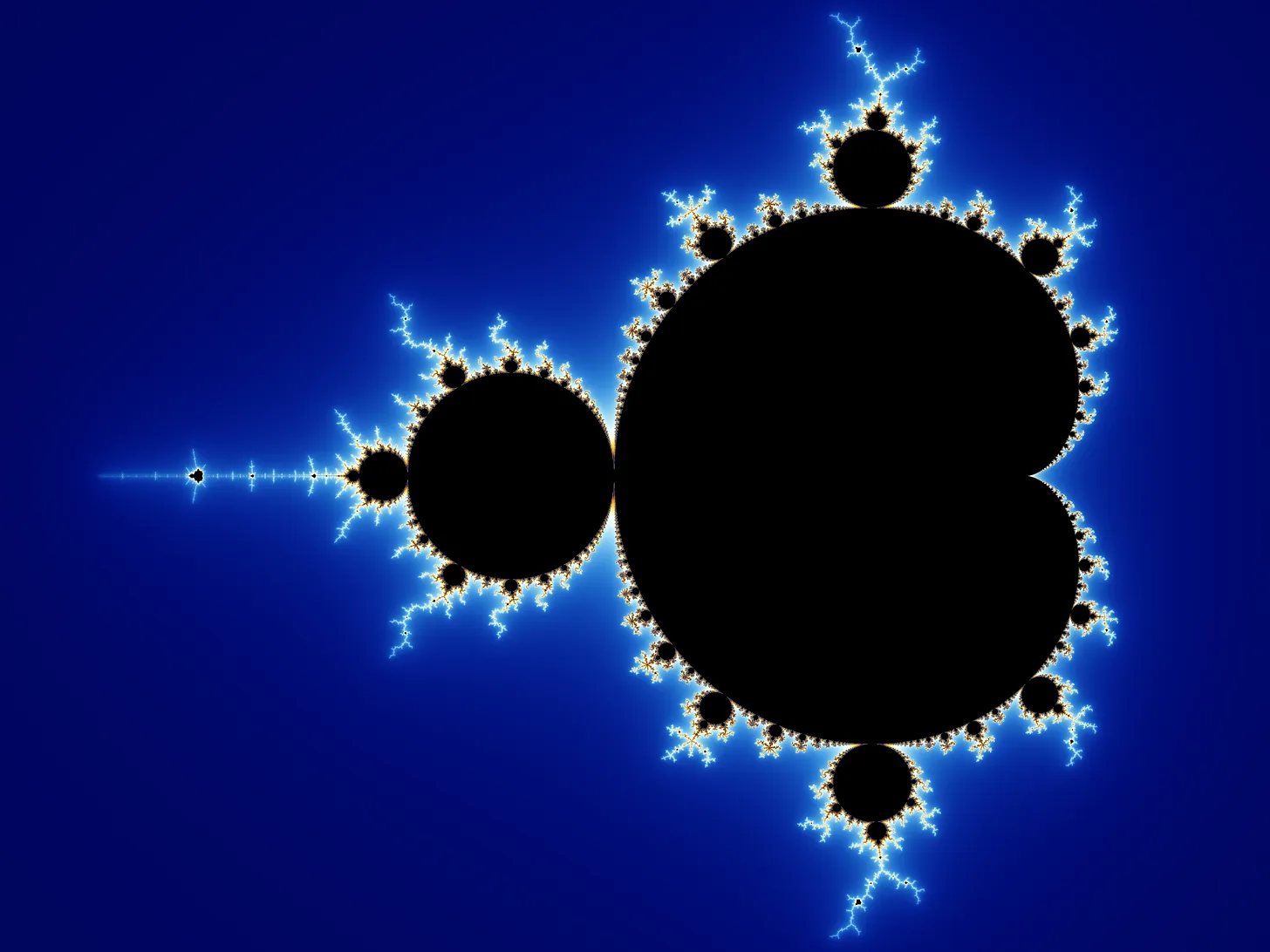

I’m fascinated by the idea that seemingly small choices can have profound and unpredictable effects on the state of the future. In the study of dynamical systems, this is characterized as the phenomenon of chaos. Imagine we had a single equation that could perfectly predict how the universe would unfold for all of time. All it would need to work is a set of inputs – i.e. the initial conditions, in the parlance of mathematics – that described the current state of the universe. Feed the equation variables like number of living stars, the density of every known planet, the emotional state of all sentient beings, and anything else we can measure, in return for a singular expression that contained everything everywhere all at once.

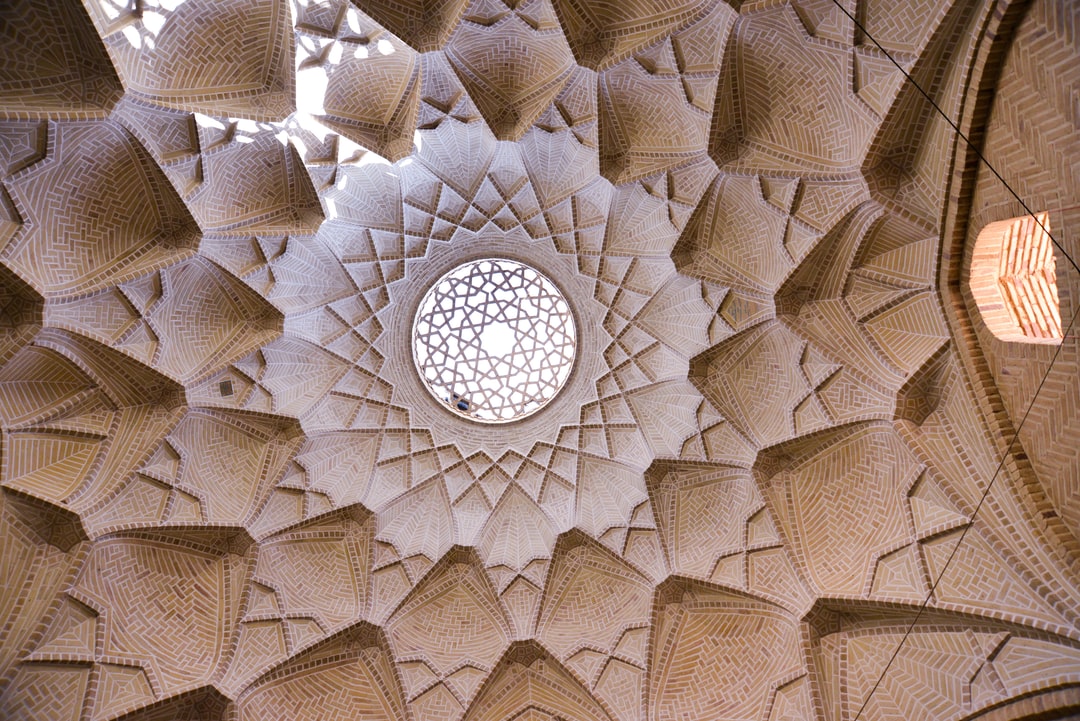

Except that, even with the God equation, our predictions would fall short due to the imperfect precision of our measurements. We would also need the hand and ruler of God in our attempts at total certainty. But even then there are infinities that are, mathematically speaking, bigger than others, a strange truism that ultimately undermines our measurement efforts. What we actually get for all our counting and sizing up of things are outlines, a general arc but not the arc itself, in the limit of time. We gain insight into how the future might turn out, but looking more closely at the system gives us no further clarity on the true state of universal affairs.

We never really questioned if the equations themselves were dynamic in my dynamical systems class. We just assumed that our expressions captured the important aspects of the systems we sought to describe. But what if what was important could change and therefore elude the mathematical cages we had constructed? Chaos is not the same as randomness, which is surely a feature of the universe. The equations we had didn’t account for that.

Saturday afternoon. I’ve just finished reading a chapter from a statistics text on p-values. It’s the fiftieth time I’ve had to familiarize myself again with the concept and its pitfalls, though I could be doing much worse things in science.

I leave the bookstore with three books in tow. The sun is beaming through clouded skies, leaving me under hails of light that pattern the sidewalk in a dance with the trees. Five pages into Bewilderment, I’m holding back tears on an empty park bench.

Watching medicine fail my child, I developed a crackpot theory: Life is something we need to stop correcting. My boy was a pocket universe I could never hope to fathom. Every one of us is an experiment, and we don’t even know what the experiment is testing.

My wife would have known how to talk to the doctors. Nobody’s perfect, she liked to say. But, man, we all fall short so beautifully.

What we know is a game of numbers in the mind of many scientists. The more experiments we run, the more certain we can be of our results. But no two experiments are exactly the same, surely a confound in this line of thinking. Let time take care of the uncertainty, they say, to which I respond: we will all be dead in the limit of time.

Have I played the game long enough to know if I am different now in comparison to all previous versions of myself? Would a within-subject null hypothesis test yield a statistically significant p-value? Or is this a false positive, a random fluctuation in the data collection process that has led me to an erroneous conclusion about how I feel?

People and cars are blurring past me. Behind me there is music. Birds are singing, when I listen closely enough to hear them. I put on my sunglasses, close my eyes, and let the world in. The tears begin to fall, a lightness fills my chest. I lean and zoom into the moment, not to predict or control the future, but to know the meaning of happiness.

Links, Music, Miscellanea

Being Alone. An essay on being alone as a portal toward building the relationship you have with yourself. I liked it because it didn’t treat aloneness as an end in and of itself, but rather as a way to get more comfortable in your own skin. This was a much needed read because loneliness has felt more poignant lately. Accepting it and focusing on rediscovering and creating my own joy, I’m starting to feel good in it again.

I loved this recent piece Ava the great Bookbear wrote, what we find in other people. What really resonated with me was this:

The way I used to relate to people was so much about completion, about craving. I didn’t understand that you can never get enough of something you don’t really need. If you’re blind to the wholeness that’s already present, you’ll never find it in other people. When you see it you’ll see it in everyone.

I’m still constantly learning how to see this in others and myself, the undeniable wholeness that already exists.

I rediscovered Masaaki Kishibe recently, an acoustic guitarist and composer from Japan. He has a distinct, lulling sound to his compositions. I’m learning this song in particular, Light: