Sometimes a rhyme is good.

Avoid all shrouds and sometimes

repetition too. Subtract words

as needed, maybe all of them.

Keep one ear close to the page

and listen

to the heartbeat

of every word, every space,

every line; see how lines

define

and break

and keep steady the pace

of a poem. And remember that

heart is at the center of it all.

One moment I’m a philosopher, all words

and fat with truth. The next I’m a poet

moonlighting for something new to say.

I’ve tried on the certainty of equations

since they promised me the last word.

But I liked the birds instead, every word

of theirs a spell that guarantees

the truth of my existence,

that truths are truisms

only sometimes true,

that Truth itself lies

within and beyond

what can be said

and has been said

with words.

What’s real

is not

ideal.

Peel

an orange

& feel

its parts,

how easily

the whole

breaks

apart

& still

retains

its tart,

perfection

an orange

in every bite.

Like life, you kept finding your way through my

walls despite how many times I squished you

nudged you onto paper mail to leave you

out in the harsh winter air, where confused

you wondered what happened to the warmth of

a home that once housed your black-red body.

You looked at me with curiosity

the other day as I was about to

sweep you away. You crawled along the top

of my couch, and when I approached you turned

your body, antennae, and zigzagged legs

at me as if you knew what was coming.

In a funny way you give my days shape

consistency in my daily motions

meaning I am not creative in how

I get rid of you from my empty flat

always with guilt and a pinch of remorse

because you are there during lonely nights

in the vents, hiding in the windowsill,

always available like morning light

to spring me from my longing, to wake me

into something just beyond the outline

of my well-traced but unknown interiorities.

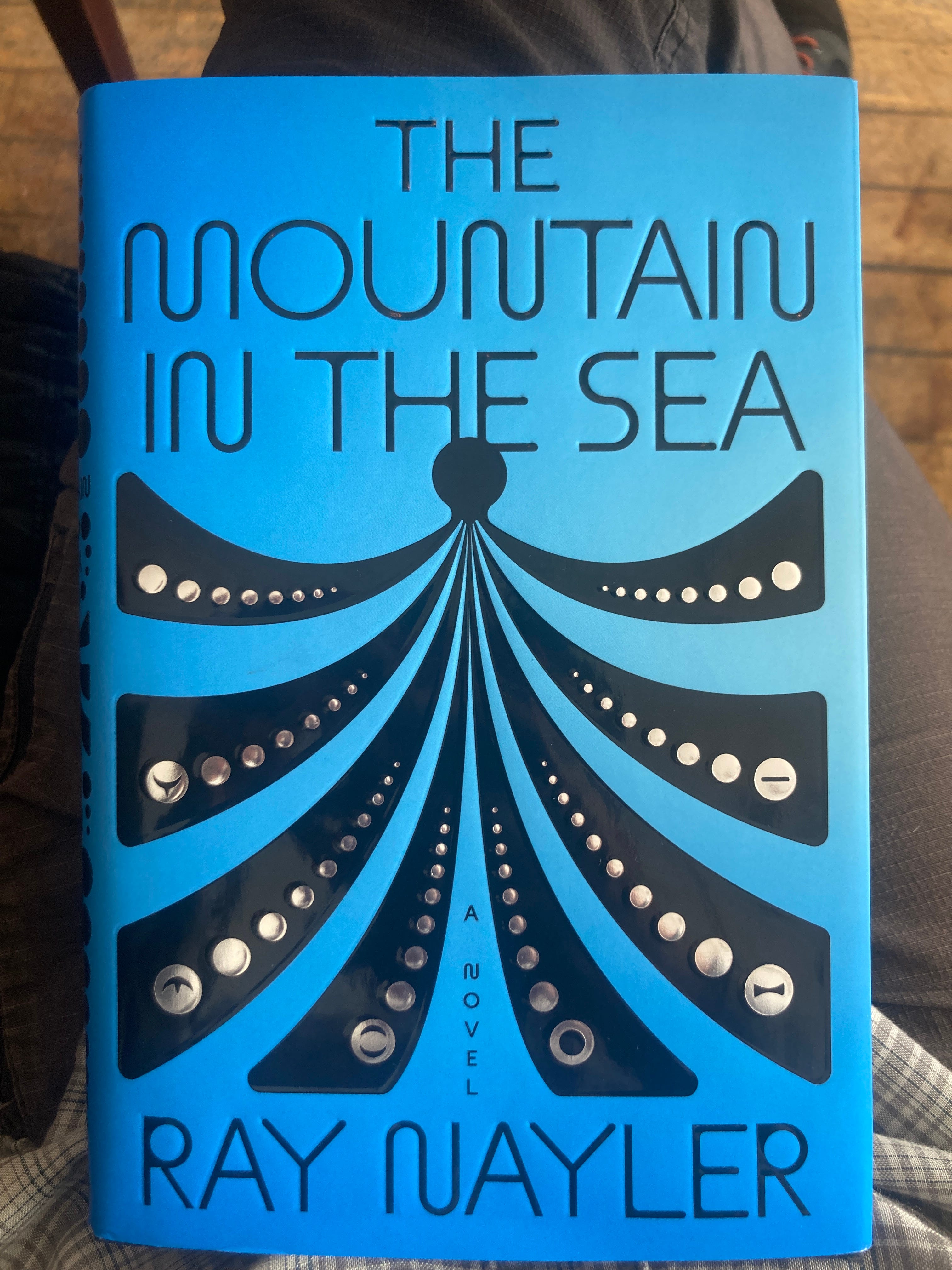

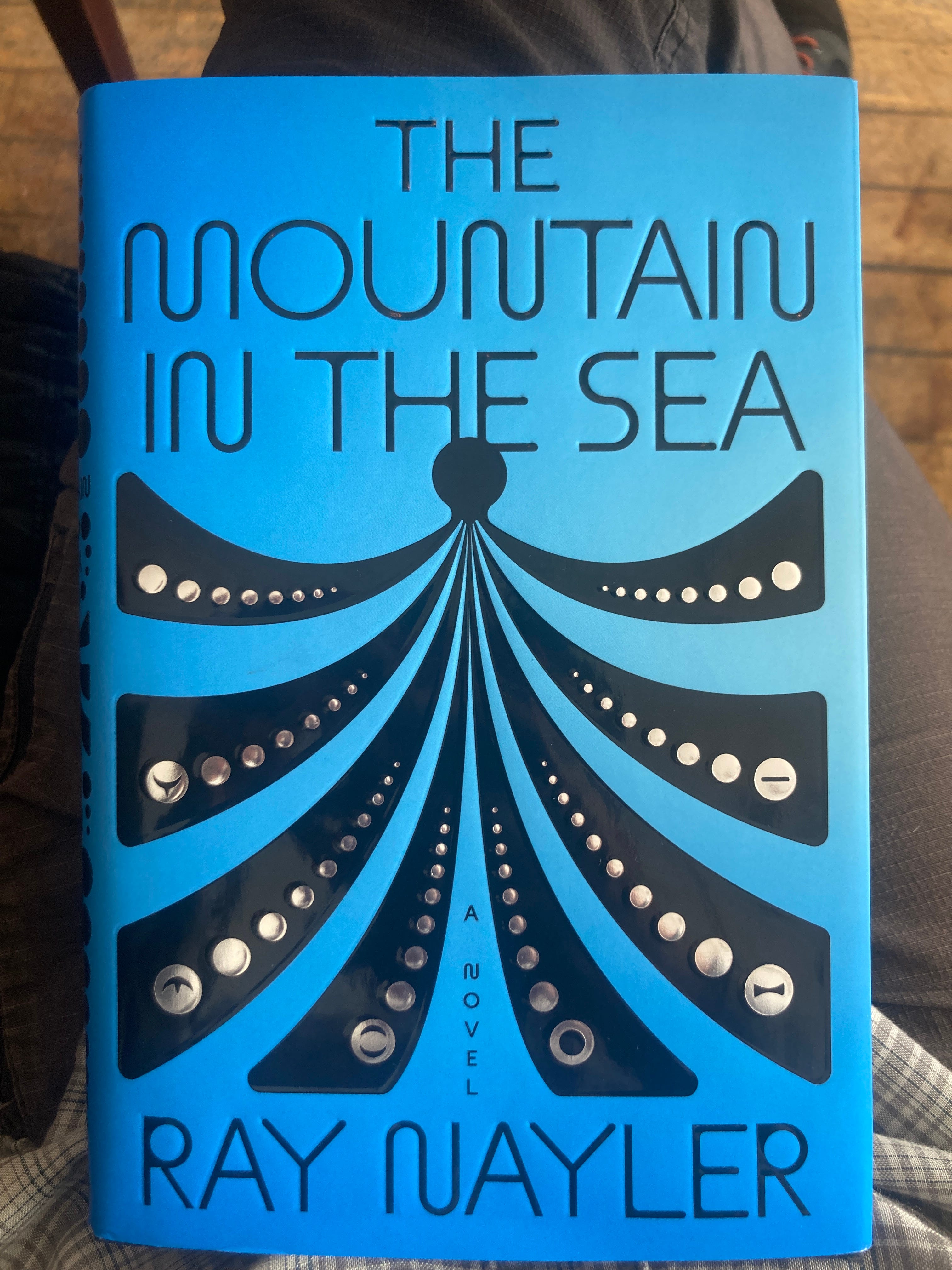

Sometimes you read something in a book that is so moving that you can’t help feeling that something in you has literally shifted. This was the effect of chapter 28 of Ray Naylor’s “The Mountain in the Sea.” The book is, in part (there is so much in here!), an exploration of AI, octopuses (yeah, it’s octopuses, not octopi, due to the Greek origins of the word), and the ends that sentient beings will go to preserve themselves.

Sitting across from me is a child with a book in hand. This sort of thing fills me with an unreasonable amount of hope for the world. She’s engrossed by the colors and a sea of static faces, as if in rebellion against the digital ocean designed to captivate us more than the ocean itself. We are drowning in the currents of the former, without any sense of beauty and movement from the latter. Fully garbed in pink, she’s delighting in showing her mother and her mother’s friend the simple happenings that populate the pages. The words are animating her young mind and soul. Her voice has filled the entirety of the café, as she bounces between being herself and the seeming fictions. The line between the two is fuzzier than we think. I don’t want to moralize, but I feel that the parents are doing something right. I see it in the ease of the child’s laugh, the joy that spreads across her lips as she plays in the ocean of her imagination. It’s thanks to her that I feel my younger self has been freed to dive aimlessly into The Mountain in the Sea, to meander in a world inspired by our own.

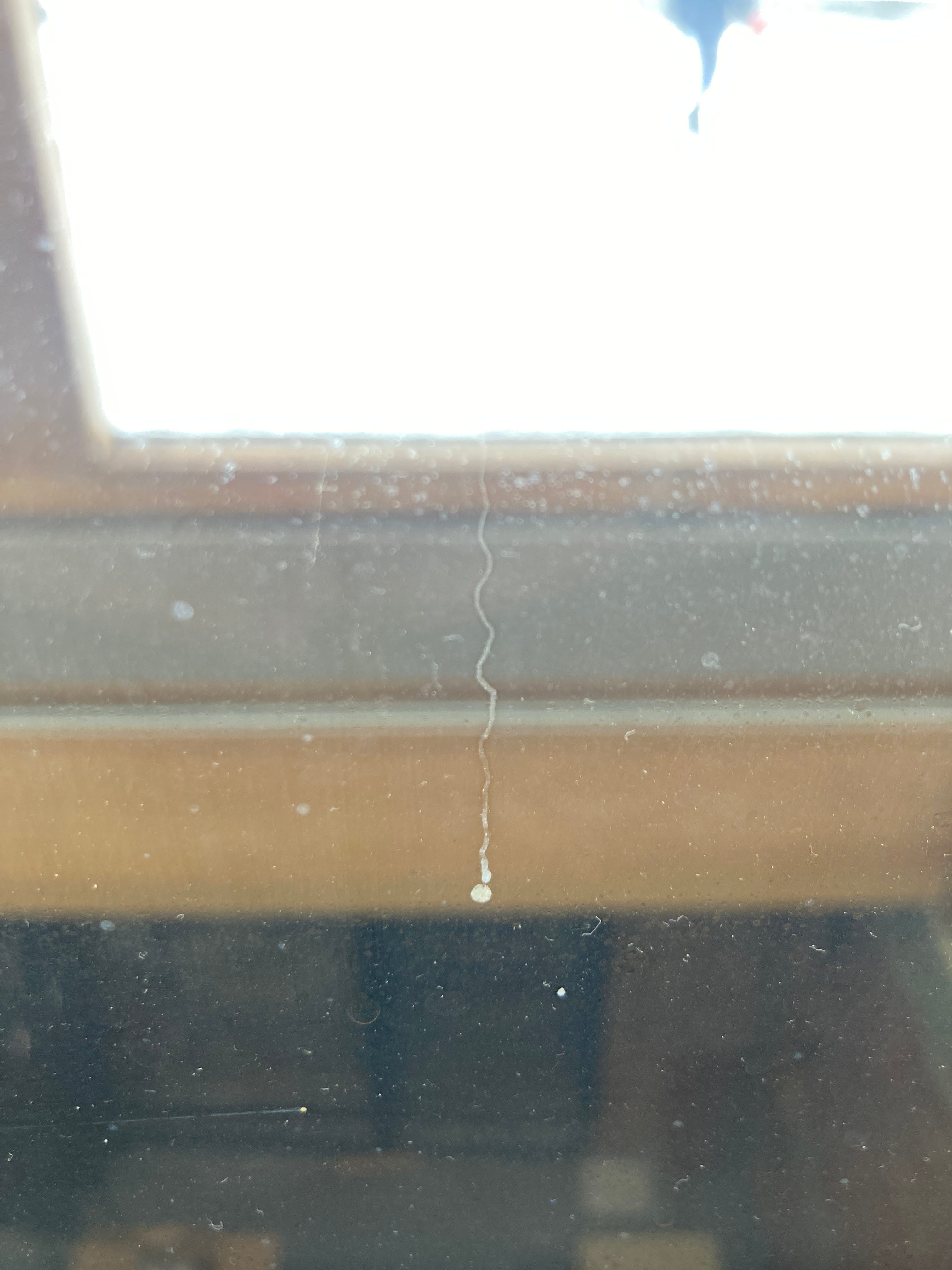

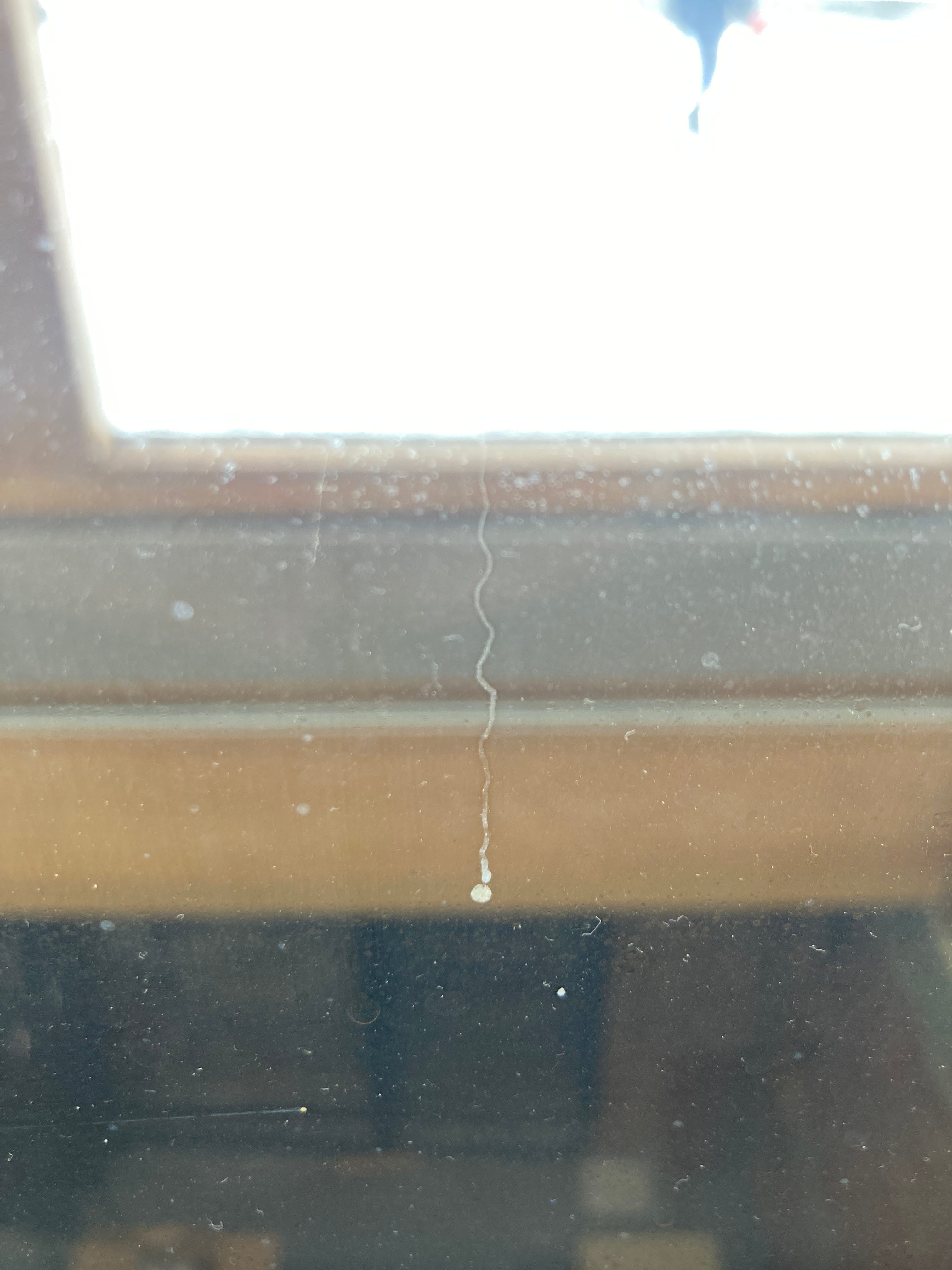

There is delight in the way our minds find spurious associations between things. I was looking out the window of a coffee shop at a heap of snow recently formed by an overnight storm, when suddenly my eye caught it: a small white dot on the window, and above it, a trail following a sud of soap. “Baby making in progress” was my first thought. Baby making in progress. I rolled my eyes and laughed at myself. Jesus, I thought. He would be disappointed. I was then brought back to high school health class, which reminded me of the young female teacher my friends and I oogled on the daily like helpless puppies. I don’t think we learned much in that class, but I do remember how strange it was to watch the movie on baby making. You know the one. Heavily pixelated, generic voiceover, 1990s feel to it. We, the freshmen, were deemed mature enough, supposedly, to bear witness to the miraculous, complex machinery of our collective conception. I watched, mesmerized, as animated swarms of sperm raced shoulder to shoulder in an attempt to create new life, to give themselves over for the continuation of our species. Not all of them would make it the narrator said with dramatic indifference. But, as if it were inevitable, there would be an eventual winner. There had to be, he said. That’s the promise of obsessive single-mindedness, singularity of purpose. All they ‘wanted’ to do, all they ‘lived’ for (how lovely and unavoidable our tendency to anthropomorphize) was this. And, perhaps, to stun naive, unlearned high schoolers in Southern California. I was a hopelessly lost child who knew only of video games and brotherhood. That was life, just me and the boys (though sometimes girls were involved too). But perhaps I wasn’t so different from the little swimmers that trained day in and day out within the confines of my developing body. They were my first clue that you didn’t need much to get far in life. All you needed, maybe, was intention and the willingness to swim. How delightful it is then that I am where I am, a decade and a half later, giving thanks to gravity, a watermark, a dried up soap sud, and the beautiful machinations that animate our minds.

In Burlington you will find a dog waiting for you around every corner. Try to hide on Hyde Street and you will eventually be barked at by Foxy the coyote-looking dog. Pop into Kru Coffee and ten of them will be waiting in line with you for your daily drip. You cannot escape them when you’re out and about in the city wilds, and that is a good thing, a very good thing.

Snow: so much like sand. The way it clumps, every molecule hanging together, shaped by the objects it falls on, are nothing without the whole. Its individual motes are sparkly and luminous under certain slants of sunlight. Much like us, they rely on the sun for their beauty. Snow and sand form deserted deserts in the night, free from the people and light that gave them attention. Who are we without the eye of another? Is the existence of everything instantiated by—dependent on—the existence of everything else?

I am sitting at a café (so French and proper of me to include the accent over the e) that I frequently visit, a black coffee and The Book of Delights in hand. Ross Gay is a genius and delight. Every word of his makes me smile. (So wonderful that words can do such a thing!) I’d like to meet him and see the world through his eyes. His book is the next best option. Right now the sun is beaming through the window, windows I’ve gazed through countless times, as snow melts from the grooves of the rooftop above me. Who am I telling this to you ask? You, the precious table I always sit at. How many others have spilled coffee upon your surface? How many crumbs of biscuit and croissant have you yourself tasted, each colored by the mouth of tasty, chatty, quiet, solemn strangers, lovers and potential lovers, people with fates yet decided, all over your solid body, a catchall for leftovers and conversation and contemplation? Every day is new to you, even when it’s me and my crumbs again. Familiarity doesn’t scare you. All you need is attention, because despite all appearances, you are quite neglected, though it doesn’t make you too unhappy if you had to be honest, especially those split seconds when the barista is in the bathroom and the patrons are out and off to do something responsible with themselves (like work and taxes), leaving you to bask in the sun and silence, right until the door opens again and a stranger like me sits with you, perhaps to write out these exact thoughts, which are to be enjoyed over other surfaces, in beds, on screens, with coffee and a biscuit perhaps, over other wooden tables somewhere else in the world.